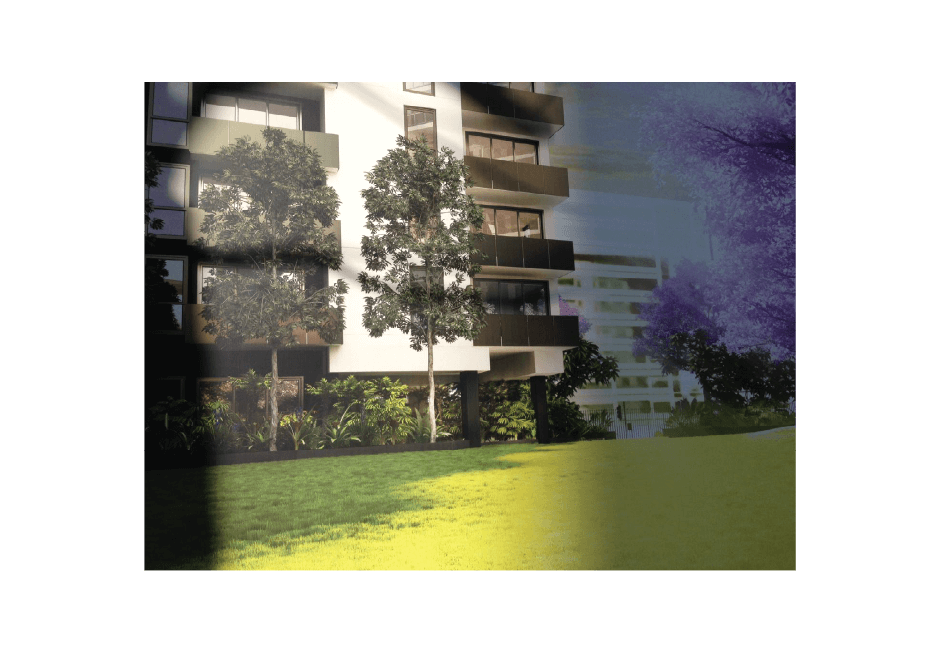

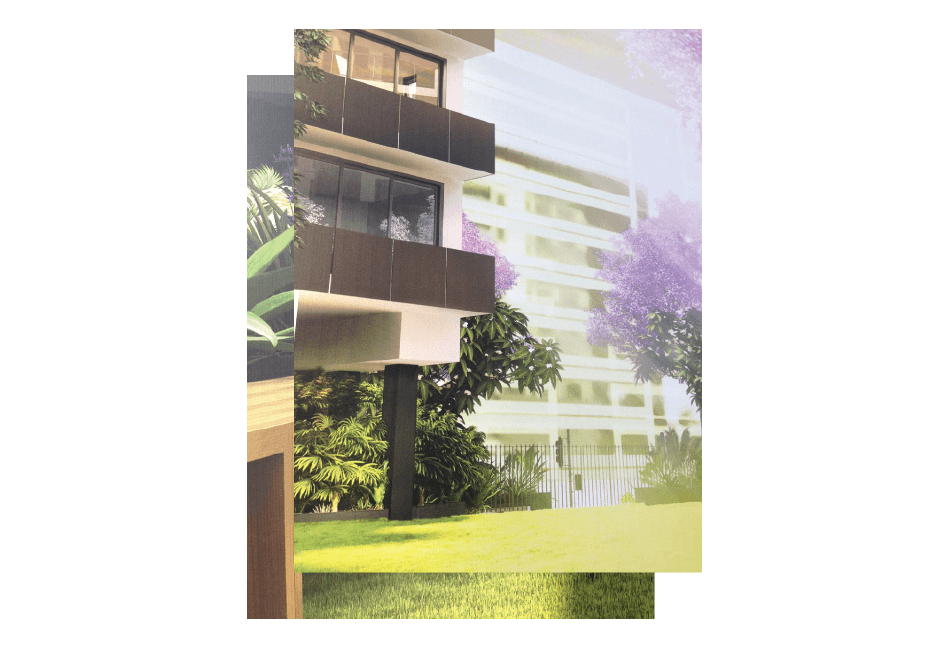

I became intrigued by the large artworks installed outside construction sites portraying ‘artist’s impressions’ of new developments. These digital drawings of the completed construction are often beautifully composed and rendered, with stunning attention to detail. They usually include clip art of tiny people to provide examples of how the community will use the space and where they will sit, walk, eat, read the paper, purchase a coffee, converse and interact with the design.

I see these ‘artist’s impressions’ as visions of the future. Perhaps not recognizable as being the sky-cities, climate domes and space-stations of popular science fiction future fantasy, these visions are portraying the future of a few short years ahead. But I think they make an important comment about how we want to live.

The first telling sign is their commitment to perfection.

The way in which natural forms are included in these renderings is particularly interesting, and can give us a clue about our idealistic relationship with nature.

Grass, trees, plants, flowers, shrubs and even sunlight is allowed in our future vision – on the condition that they are perfect, and in no way betray themselves as being faulty, primitive, weak, sickly, messy, unpredictable or uncontrollable. In other words, nature is welcome in our future vision, just as long as it isn’t too natural.

Thinking and researching on this topic has led me to an even more interesting observation/critique:

We are striving for an aesthetic utopia, free from anything which might remind us of our naturality, and thus our mortality.

For centuries, we humans have celebrated the spiritual and intellectual sides of ourselves, separating ourselves from the animal world and thus lifting us closer to the divine. This quest is a collectively distinguishing act, embedding humankind with purpose, meaning and superiority over the natural world.

Historically, organized religions and spiritual belief systems have satisfied our need to justify our existence – a place to ignore our physical selves – our bodies, which are traditionally sinful, corrupt, animalistic, licentious and which consistently betray us. The more we can surround ourselves with reminders of our own importance and superiority, the more we can be distracted from thoughts of our animalistic heritage, our imperfections and our mortality.

The next level of observation within the study of these digital renderings is, of-course, the virtual nature of them. How different is a digital rendering of a new imagined apartment block to a digital rendering of a virtual world or a science fiction future fantasy? Are virtual worlds our new temples? Do we dive into virtuality in order to escape our physical/natural shortfallings, worshipping at the alter of computer generated perfection? Perhaps we are unwittingly celebrating in a utopian vision of life where everything – including nature – is controlled.